Covid-19 stopped live performance art in its tracks more than a year ago. But the camera has continued to mediate between the audience and the artist, revealing processes, and allowing us access to challenging and thought-provoking work. Elissavet Ntoulia explores powerful performance art in still form.

March 2021 marked the first year AC (After Corona): a new era in which our certainties have been shattered by a contagious life form invisible to the naked eye. Disease, like art, is made visible in its representations: the sick bodies, the tired minds, the empty supermarket shelves.

The Covid-19 pandemic saw the halt of live performance art, which remained alive in the public imagination through still photographs. In January, a photo from Marina Abramović’s famous performance of ‘The Artist is Present’ became a viral internet meme.

Bernie Sanders meme in Marina Abramović’s performance ‘The Artist is Present’ at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2010; R Eric Thomas’s Twitter.

The term “performance art” was coined in the 1960s, another time of global political and social upheaval. It described art-making that was radical and experimental and that addressed social issues more directly, compared with traditional painting and sculpture. Most crucially, it described art realised in a particular time and space, with the artist doing something live and, more often than not, with an audience present.

As such, performance art existed largely outside the mainstream art world, neither inside institutions nor the so-called ‘avant-garde’, but rather taken to the street and to those who had been systematically denied access to art.

For example, artist Lorraine O’Grady put performance into the largest black space she could think of with ‘Art Is…’. She and her crew joined Harlem’s African American Day Parade in 1983 and, jumping off their float, invited the eager audience to become the art by posing in empty, gilded picture frames.

Lorraine O'Grady, ‘Art Is…(Young Women Leaning on Barrier)’, 1983/2009.

Artists and audiences

Fast forward a few decades, and performance art has entered the institutional world of museums, galleries and art biennials. Since the 2000s and the gradual establishment of the digital in our lives, curators have seen performance art as the “medium of our time”. Rooted in the present, it offers endless possibilities for experiences by experience-hungry audiences.

However, institutions know how to deal with objects and not moments, and therefore collecting performance art has been challenging; a challenge that the limitations on ‘liveness’ during the last year made even bigger.

What happens, then, to performance when is stripped of its physicality? Has its soul of ephemerality been stolen by being captured in images, videos or when live-streamed and mediated by a camera? Is this the end of true art experiences?

Working in a public-facing museum role, I am the first to appreciate and miss terribly the often magical and indescribable moment of the physical encounter with art, the collective experience of strangers that art spaces make possible.

I am the first to appreciate and miss terribly the often magical and indescribable moment of the physical encounter with art.

Performance, specifically, can allow for a wider range of emotional and multisensory experiences. It allows the viewers’ interaction to become the piece or at least essential for its realisation, what artist Coco Fusco has described as “reverse ethnography” in relation to her performance ‘Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West’ (1992–3) in collaboration with Guillermo Gómez-Peña, performed in several locations around the world.

For this performance, Fusco and Gómez-Peña put themselves on display in a gilded cage as indigenous Guatinauis, natives to the fictitious island of Guatinaui. While they performed various rituals of ‘authentic’ daily life, the public could also pay to have them do stuff.

The audience and their reactions stumbling upon such a spectacle were key to the artists’ intentions to speak back to the history of ethnographic exhibition of human beings in the 19th century by “performing the identity of an Other for a white audience”.

Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Coco Fusco perform ‘Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West’, Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, 12 September 1992.

However, overemphasising the live or interactive elements of performance art does not do justice to its multifaceted and ever-malleable story.

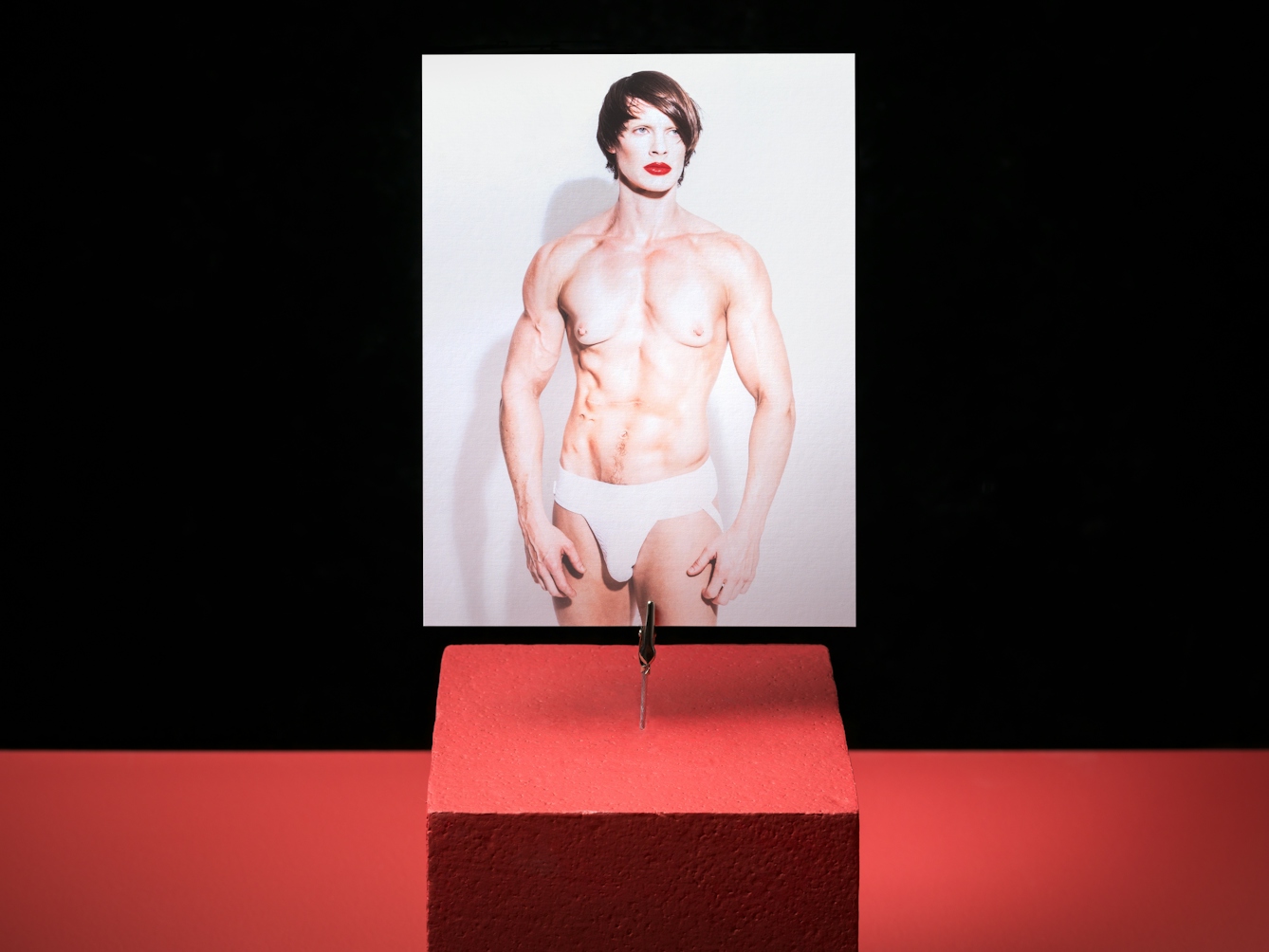

Cassils is a transgender Canadian artist, and their work ‘Advertisement: Homage to Benglis’ (2011) is on display at ‘Being Human’, Wellcome Collection’s permanent gallery that explores what it means to be human in the 21st century.

Inspired by the work of two other performance artists, the piece is a photograph created in collaboration with photographer and make-up artist Robin Black. The artist’s muscular body wears nothing except white underwear with whitened makeup and bright red lips, mixing what is considered masculine and feminine identifiers.

Cassils, ‘Advertisement: Homage to Benglis’, 2011.

The title directly links to the artist Lynda Benglis and her provocative ‘Advertisement’, in which she poses naked in sunglasses and a fake tan that matches a double-headed phallus that she holds at the entry of her vulva. The image was to accompany a review of her gallery show ‘Knots’ in the art magazine Artforum in 1974, but after the magazine’s editors turned her down, she bought ad space at double the usual rate and was denied the coverage.

Benglis, like other feminist performers at the time, used vulgarity to show the middle finger to the macho art world. Not surprisingly, her female-to-male transgressiveness led to two Artforum associate editors resigning, feminists’ critique of Benglis capitalising on her body’s attractiveness, and an all-round scandal.

Image and identity

Decades apart from their inspiration, the internet allowed Cassils to bypass mainstream art publications, releasing their transgressive photos online to gay fashion, art magazines and via their own publication, the ‘Lady Face/Man Body’ zine. However, similar reactions to those greeting Benglis’s photo make such work as political and essential as back in the 1970s.

When on show in the 2016 exhibition ‘Homosexuality_ies’ in Germany, the image became the subject of complaints by local LGBTQI+ groups, who called it “monstrous”, while the Deutsche Bahn railway company refused to use it at train stations as a promotional poster on the grounds of it being “sexualised” and “sexist”.

Cassils’s ‘Advertisement’ is also a snapshot of the 160th day of their six-month performance piece ‘Cuts: A Traditional Sculpture’, during which they gained 23 pounds of muscle over 23 weeks via bodybuilding and nutrition. They documented the transformation by taking photos of their body from four different vantage points, exactly like feminist artist Eleanor Antin in her performance ‘Carving: A Traditional Sculpture’ in 1972.

While Cassils cuts their biologically female body (a nod to the absence of the surgical cut) to push the limits of the gender binary, Antin carves hers (a nod to the ideal body form of classical sculptures) to show the limitations of beauty standards via a month-long starvation.

Cassils’s reiteration of Benglis’s and Antin’s performances are testimony that the exhilarating legacy of performance art can be found as much in documentation and stillness as in movement and transformation.

Living and working in Los Angeles, the land of image-obsessed celebrities, during a period that “if it’s not in social media, it hasn’t happened”, Cassils understands both the power of performance and image, especially when it comes to identity and gender. Like many contemporary artists, they work across media and shape their performances’ documentation as part of a whole, but they are also executed as pieces on their own right.

These artists are aware that live performance’s intimacy cannot be replaced or replicated, but its ability to expose the processes of life and art, transcend time and activate our consciousness and imagination is powerful via any available medium.

If there’s something that this year has taught us, it is that life does not fit into neat categories of opposites. Performance art can show us a thing or two about the freedom that can be found in the in-between.

About the contributors

Elissavet Ntoulia

Elissavet Ntoulia is a Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.

Kathleen Arundell

Kathleen is a freelance photographer working in the culture and heritage sector. She works in a range of museums across London, and loves all things science and art.