Could your facial features tell how likely you are to get sick? Francis Galton and Dr Frederick Mahomed failed to prove this theory, but this didn’t dissuade Galton from a career in eugenics. University College London curator Hannah Cornish tells the story of a huge study from the early days of evidence-based medicine.

How tuberculosis became a test case for eugenic theory

Words by Hannah Cornishartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

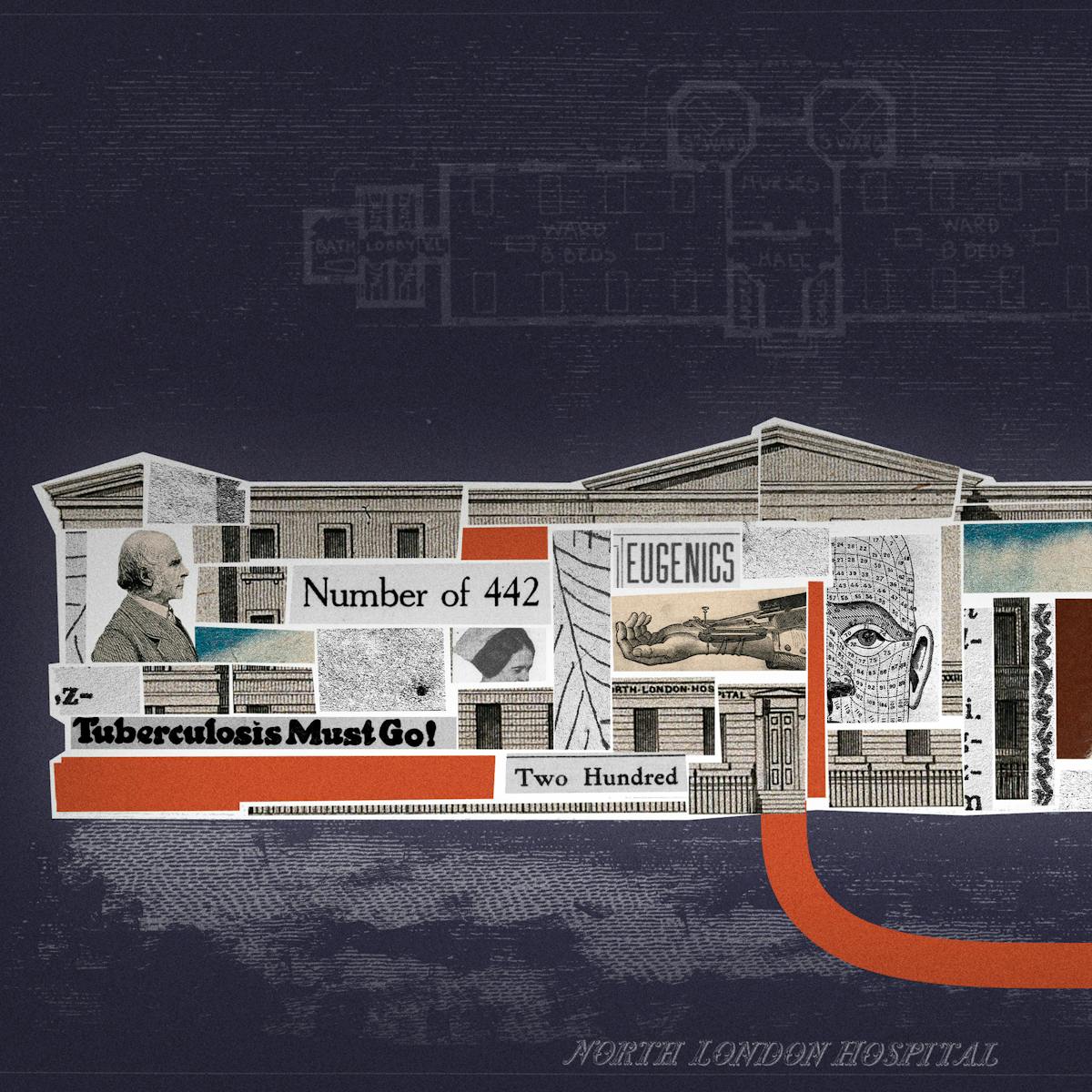

In 1881, Frederick Akbar Mahomed and Francis Galton started a project that fed into one of the first nationwide epidemiological studies. It also fed the beginnings of eugenics, a movement that has caused immeasurable harm across the world ever since.

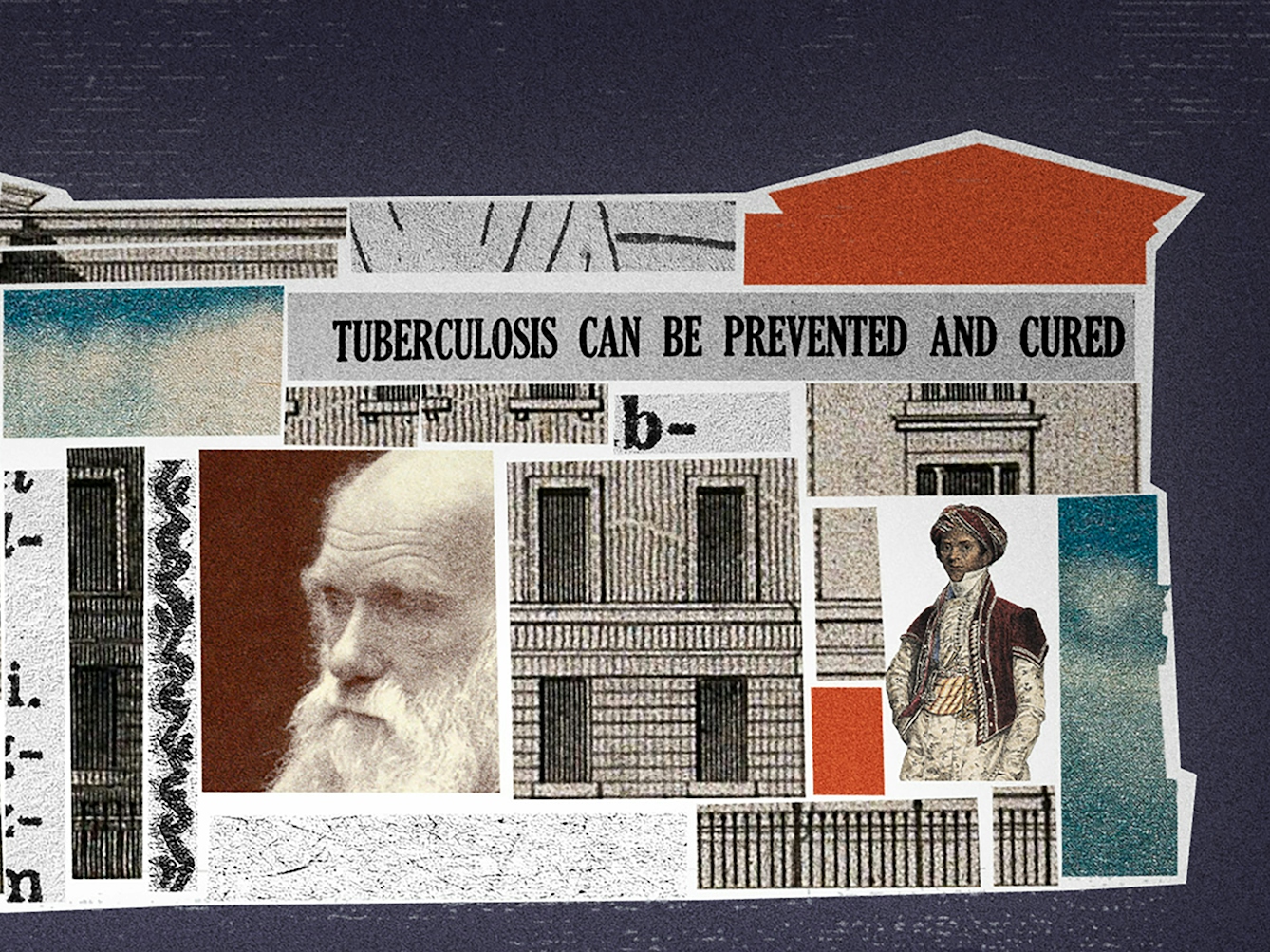

Galton came from a wealthy, highly educated Midlands family. He had a fascination for measuring people (anthropometrics) and an intense interest in heredity, inspired by his cousin Charles Darwin’s work on natural selection. He was also interested in physiognomy, a theory that a person’s character can be read from their facial features. To investigate this, Galton invented a method of overlaying photographic negatives to produce composite average faces.

Mahomed was a doctor from an English, Indian and Irish background. His grandfather was the famous Sake Dean Mahomed, an Indian traveller, author and entrepreneur who introduced Indian cuisine to Europe. Frederick Mahomed made important improvements to the sphygmograph, a device that measures the pulse and blood pressure, and produced groundbreaking work on blood pressure and kidney disease.

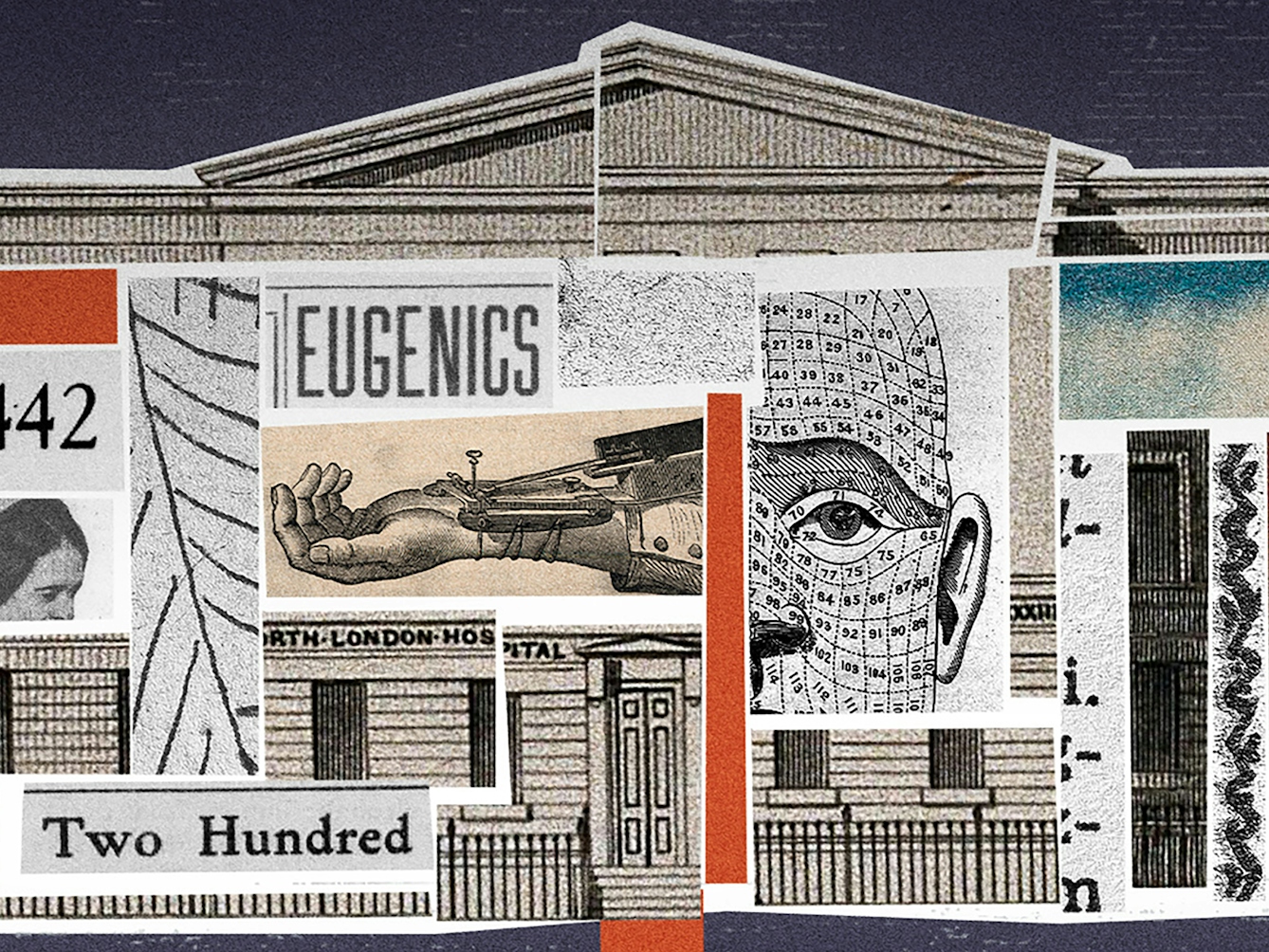

Galton was interested in the physiognomy and inheritance of disease, and joined forces with Mahomed to prove an idea that was conventional medical wisdom at the time: that a patient’s appearance could show which diseases they were susceptible to. They chose tuberculosis as their test case.

“Was there an ‘inherited taint’ that predisposed people to infection, and if so, what could be done?”

Could facial features predict disease susceptibility?

Tuberculosis was a leading cause of death in 19th-century Europe and America. Scientists knew that tuberculosis spread faster in areas with poor housing, diet and sanitation. Doctors agreed it was infectious but thought it could also be passed down in families. Was there an “inherited taint” that predisposed people to infection, and if so, what could be done?

Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs, where it causes a chronic cough, fever and weight loss. It can occur in other parts of the body too, and when it attacks the lymph nodes in the neck it is known as scrofula. Many doctors believed that patients susceptible to tuberculosis of the lungs (tuberculous patients) were thin and fragile, whereas those susceptible to scrofula (strumous patients) were stocky and robust.

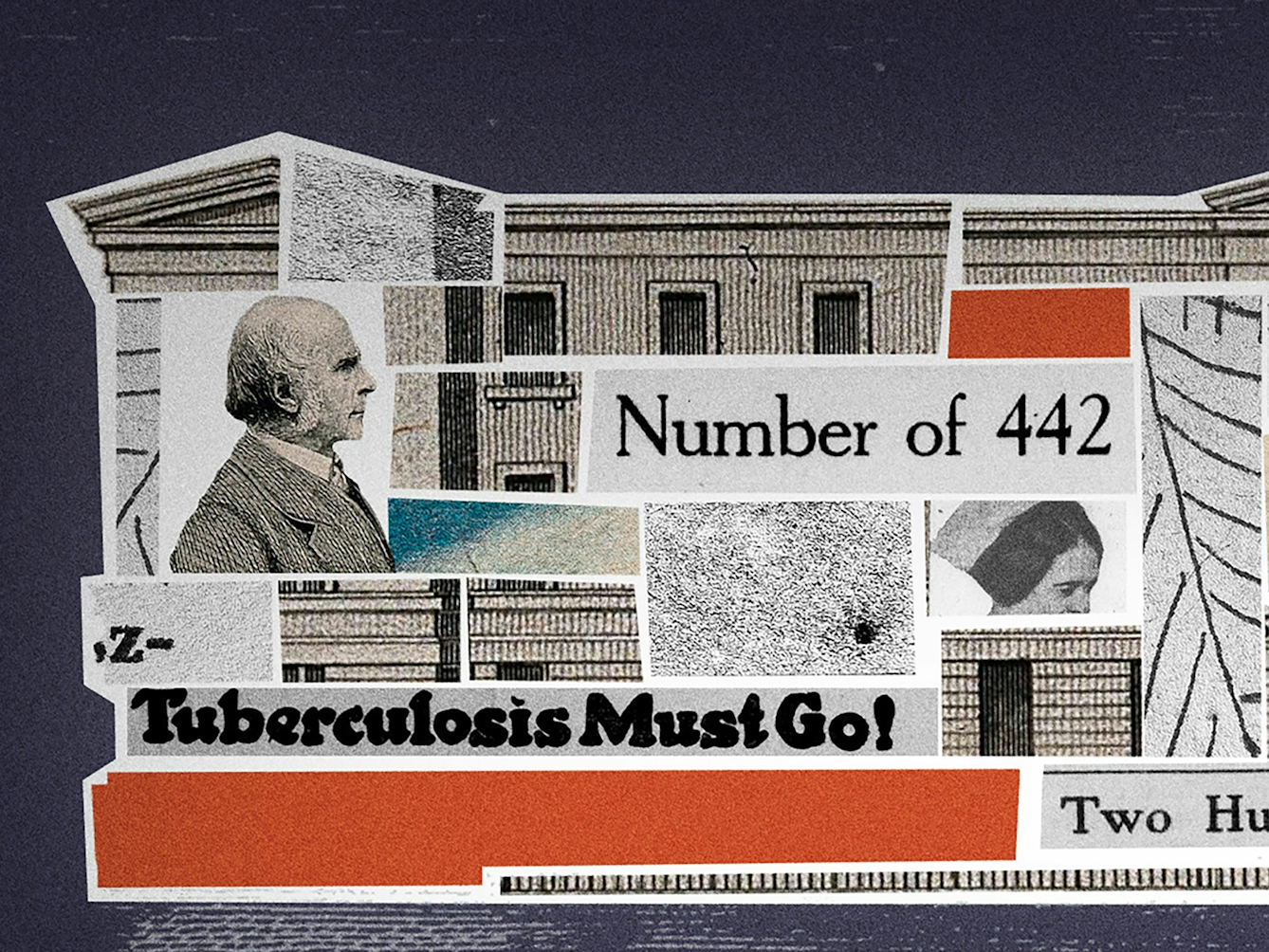

Throughout 1881, Galton and Mahomed arranged for 442 tuberculosis patients to be photographed in London hospitals. They also commissioned photographs of 200 patients suffering from other diseases as a comparison.

The results were disappointing. There was no evidence that it was possible to predict the type and severity of tuberculosis from the patients’ facial features. The faces of tuberculous patients were no more delicate-looking than the faces of any other patients. Despite this, Galton speculated that patients with delicate, oval faces were likely to be susceptible to all disease, and he maintained it was an inherited or ‘racial’ characteristic.

“Throughout 1881, Galton and Mahomed arranged for 442 tuberculosis patients to be photographed in London hospitals.”

Personal data for public purposes

Undeterred, Galton and Mahomed moved on to a more ambitious project. In 1880, Mahomed wrote a letter to the British Medical Council proposing a new scheme to collect patient data for the public good. At the same time, Galton was developing methods to collect information about the public through measurement and questionnaires.

In 1882, their work resulted in the Collective Investigation Committee of the British Medical Association. This forerunner to modern epidemiological study aimed to collect data about disease from doctors across the country. Mahomed hoped to gather vital information about incubation periods and disease interactions.

A parallel project was set up by the British Medical Association to distribute ‘Life History Albums’ to the public to collect information about health and inheritance in individual families.

Galton and Mahomed worked with the Collective Investigation project from 1882 to 1884. The first diseases studied were rheumatic fever, cholera and pneumonia. The data were widely used in publication and similar schemes were instigated around the world, such as a study of the 1907 polio epidemic in America.

He called this theory ‘eugenics’, a plan to solve the ills of the world by breeding better people.

On leaving the committee, Mahomed began a project combating homeopathy and dangerously unregulated medicines, but this was cut short. In 1884 he contracted typhoid from a patient and died, aged only 35. His obituaries mourned the loss of a talented and energetic doctor with huge potential.

“It turned out that heredity had little to do with the spread of tuberculosis: poverty was (and remains) the main risk factor.“

It is possible that his contributions are not well known because of racism in the scientific community. Certainly, Mahomed’s appearance and background was often remarked upon, and it was Galton’s name alone that appeared on the ‘Life History Album’, despite Mahomed being the driving force behind it.

The discredited ‘science’ of blaming heredity

In 1883 Galton gave a name to the ideas about heredity that he had been developing for years. He called this theory ‘eugenics’, a plan to solve the ills of the world by breeding better people. While Mahomed had been fighting pseudoscience, Galton was creating one. Galton’s work is also not as well known as it might be. In his case it was his association with the eugenics movement and the subsequent horrors of Nazi “race science” and the Holocaust that led to his name slipping from public view.

But what of the eugenic control of tuberculosis? On 24 March 1882, only a few weeks after Galton and Mahomed published their results, the German doctor Robert Koch identified the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. It turned out that heredity had little to do with the spread of tuberculosis: poverty was (and remains) the main risk factor.

This did not stop speculation about a eugenic cure. By the early 20th century, tuberculosis was back on the eugenics agenda.

At Charles Davenport’s Eugenics Record Office in the US, researchers were determined to steer tuberculosis research back from infection to heredity. They proposed that tuberculosis should be one of the conditions that should prevent people from marrying or from entering the United States. American eugenicists claimed tuberculosis was most prevalent in groups that the country should discourage – notably disabled people, the poor and people of colour. They lobbied for enforced sterilisation of tuberculosis sufferers.

It is an unsettlingly familiar scenario. Just as in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, marginalised groups were suffering disproportionately from a deadly infectious respiratory disease, not helped by researchers who were looking for racial or genetic differences to explain it, while downplaying the effects of poverty and structural inequality.

The history of medicine is complicated, and not always a linear progression towards better treatment. Doctors and scientists are humans with their own biases, and medical research culture can perpetuate bad medicine and inequality, just as it can bring life-saving innovation.

About the contributors

Hannah Cornish

Hannah Cornish is the curator of the Grant Museum of Zoology at UCL. Her research interests include object based learning, and the history of natural science and medical collections.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.