Dr Annabel Sowemimo gives us her personal take on why you might think that the history of medicine lies entirely in the West, and also why that is really only part of a much bigger story.

The secret lives of Britain’s first Black physicians

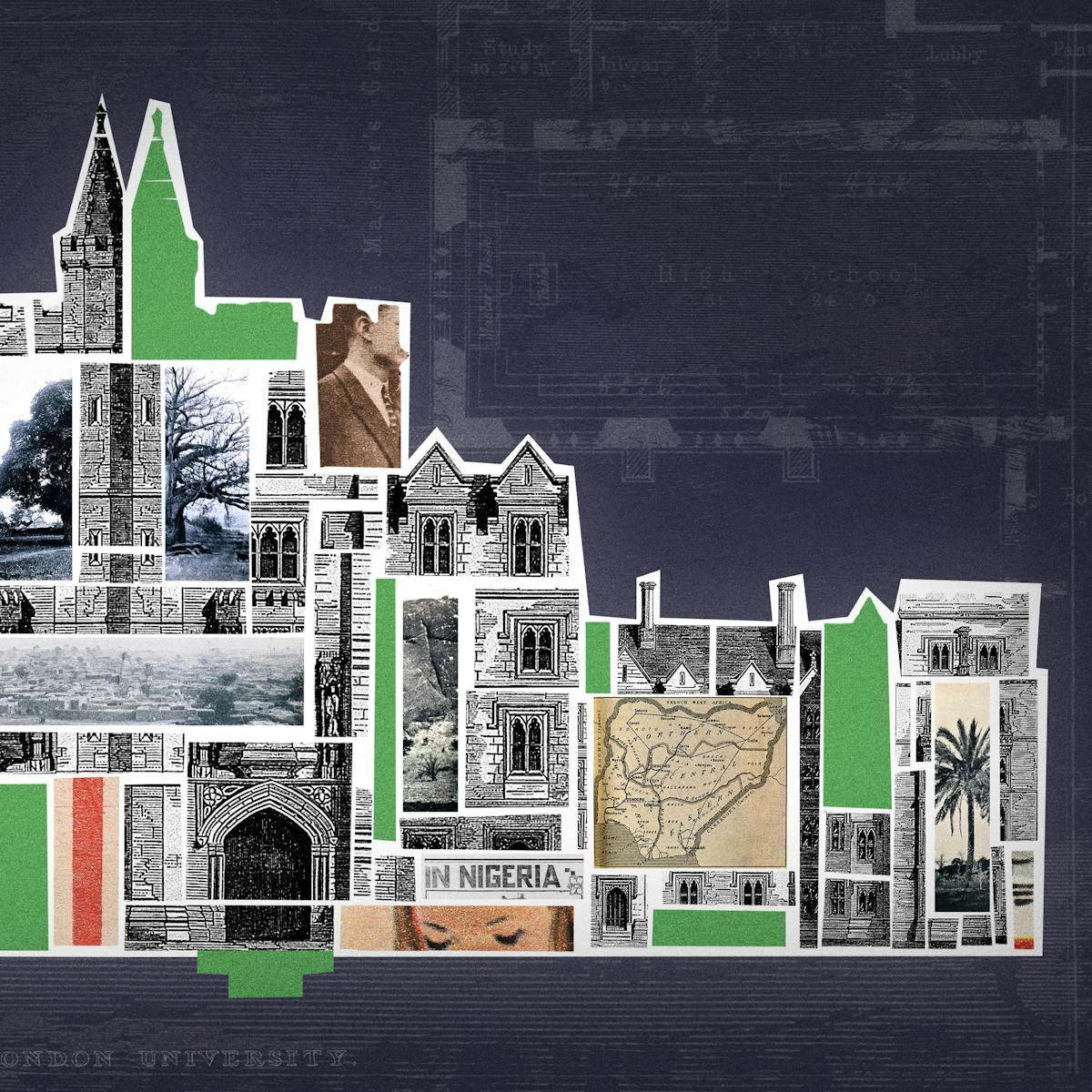

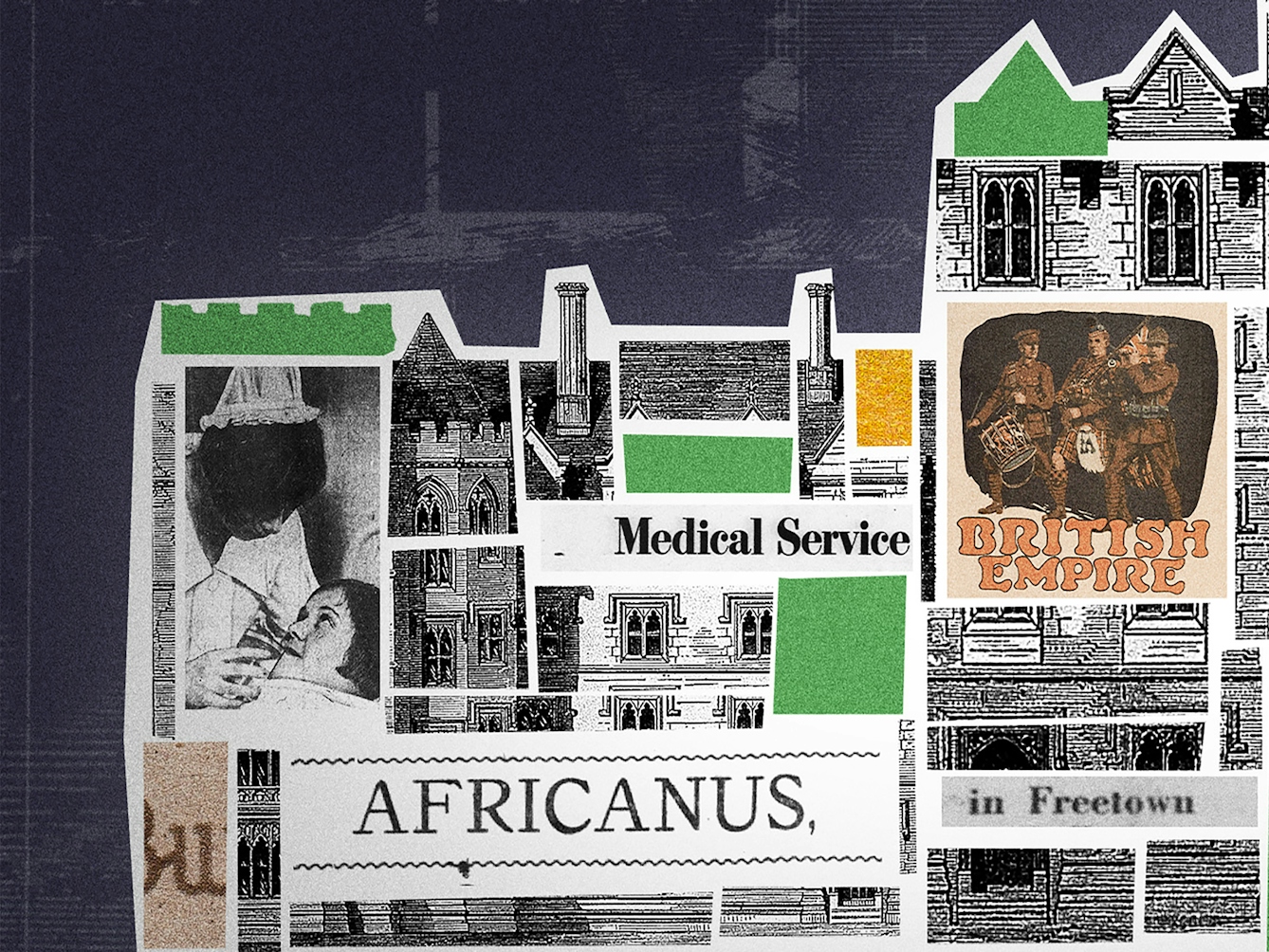

Words by Annabel Sowemimoartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

Africanus Horton Road runs through the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. My dad studied medicine here before graduating at the tender age of 21 (he was something of a child prodigy). He then moved to Britain to start his house officer training, and shortly after he met my mother, they had my brother and then me, and built themselves a life in north London.

At 13, I took a trip during the summer holidays to Nigeria with my family and we went to visit Ibadan University. I probably walked along Africanus Horton Road, but the name meant little to me. I wish it had, now I know there is so much to learn about the function of empire and race within medicine by examining the lives of some of the earliest Black British physicians.

James Africanus Beale Horton (1835–83) was born in a small village on the edge of Freetown in Sierra Leone to James Horton, a liberated slave of Igbo descent who had adopted the surname of English missionaries. Horton was educated at a local missionary school, and himself took the name of his headteacher, Beale. He then studied at Fourah Bay Institution (now College).

He was selected to go to King’s College London (KCL) to study medicine, and then to Edinburgh University, completing his thesis on 'The medical topography of the west coast of Africa, including sketches of its botany’. He later became a medical officer in the British Army, serving across West Africa.

“Horton’s views on West Africa were in many ways as much of a patchwork as his name.”

Though he added Africanus to his name to symbolise his pride in his African heritage, he remained deeply committed to the idea that white Europeans were more civilised and that British colonial rule would assist in ‘civilising’ Africa. Africanus’ beliefs often appear like a barrage of contradictions, as he wishes to remain loyal to the British colonialists who have educated him, but recognises that being a well-educated Black African stands in opposition to all that he has been taught about his own people.

A continent strangled by empire

In 1868, Horton penned his book ‘West African Countries and Peoples, British and Native’, with the subtitle ‘A Vindication of the African Race’. He recognised the growing influence of race science and its potential threat to an independent and economically stable West Africa, arguing that the formation of organisations such as the Anthropological Society of London only served to promote the intellectual inferiority of Black Africans. He recognised that the growing interest in the discipline would undermine any efforts for true independence in West Africa.

“It would have been sufficient to treat this with the contempt it deserves, were it not that leading statesmen of the present day have shown themselves easily carried away by the malicious views of these negrophobists, to the great prejudice of that race.”

Horton outlines how his own academic achievements stand in clear opposition to the limitations supposedly being placed on the “negro race”: “Let those who are interested in the subject refer to the Principals of the Church Missionary College, Islington; King’s College London; and Fourah Bay College, Sierra Leone.”

Some historians have accused Horton of regurgitating ‘ethnocentric’ analysis of West Africa and knowing too little about African relations pre-colonisation – not at all surprising, as Horton was a product of the British colonial education. Instead of criticising Horton, I am more sympathetic: his extensive colonial education only equipped him with a very limited understanding of West African cultural traditions, and he lacked insight into his West African heritage despite being raised in Sierra Leone. His colonial education did precisely what it was meant to do: restrict his world view.

The rapid adoption of scientific racism by those in leadership roles had a profound effect on the governance structures within West Africa.

“Horton recognised the growing influence of race science and its potential threat to an independent and economically stable West Africa.”

Horton’s vision for West Africa did not become a reality. Following his death, the “scramble for Africa”, a period of rapid colonisation of the African continent by European countries towards the end of the 19th century, ensued. It is estimated that the European colonial territories grew from 10 per cent in 1870 to almost 90 per cent by 1914.

European colonisers used accelerating race science as part of the justification for the “scramble for Africa” during the 19th century, which Horton had foreshadowed and so eloquently denounced in his lifetime. The rapid adoption of scientific racism by those in leadership roles had a profound effect on the governance structures within West Africa.

While African elites possessing governance positions within colonial West Africa was not uncommon in Horton’s day, the numbers declined substantially after his death. A West African Medical Service, as Horton had detailed, was established in 1902. However, it only admitted white doctors.

The radical reforms that Horton proposed for education and the economy were never realised; instead, an exploitative system that catered to the needs of Britain as the motherland were put in its place. Horton died prematurely in 1883, from a severe attack of erysipelas – a painful skin infection – and did not live to see the failure of his independence plans in West Africa.

Recentring the stories of Black African medics

Earlier in 2022, I travelled to Freetown for a conference. As part of the trip, I wanted to ensure that I saw Fourah Bay College. It was not Horton who led me there; rather, it was my own nana’s stories about her father and his work at the university.

My great-great-grandfather Dr John Randle (1855–1928) trod a path not too dissimilar to Horton’s. Born in Sierra Leone, also the child of a liberated slave, he threw himself into education and later also travelled to the University of Edinburgh in 1884, graduating with a gold medal. He became a colonial physician, writing in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet about guinea-worm infestations.

“The radical reforms that Horton proposed for education and the economy were never realised.”

Later he went on to become a Pan-Africanist and a founding member of the People’s Union in Lagos. Like Horton, Randle was a keen proponent of education, donating considerable funds to help establish the first science department at Fourah Bay.

As I walked through the campus of Fourah Bay, which lies on a hill surveying the surrounding Freetown, I could not help but think how little we speak of the Black physicians and scientists who were studying as race science and eugenics were coming to the fore. It is infuriating that the resistance that those of Black African descent mounted to colonisation, both physically and within the academic space, is consistently undermined. If we are to reckon with the dark history of colonisation, then we too need to bring the complex stories of Horton and his contemporaries into the light.

Horton’s perspective as someone educated by British missionaries, a powerful supporter of empire, yet also battling with scientific racism, provides vital historical insight into the dynamics of empire. Horton’s views on West Africa were in many ways as much of a patchwork as his name, bestowed upon him by British colonisers and followed by an attempt to carve out his own identity.

For far too long the history of medicine has been whitewashed, and the time to recentre the experiences of those like Horton whose accomplishments have been pushed into the shadows is now.

About the contributors

Annabel Sowemimo

Dr Annabel Sowemimo is a doctor, activist and writer. As well as being a sexual and reproductive health consultant in the NHS, she is also the founder of community-based organisation Reproductive Justice Initiative, formed to address the colonial history of sexual and reproductive health. Annabel is a PhD candidate and Harold Moody Scholar at King’s College London. Her first book, ‘Divided’ (Wellcome Collection/Profile Books) is an exploration of race and health.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.