‘My Hair Is Not…’ is a natural-hair campaign that brings awareness to the microaggressions and discrimination that Black people experience due to their hair. This photo story explores the experiences of eight Black women, men and non-binary people with their natural hair and how each person’s different lives and circumstances directly affect their relationship with their hair.

At the beginning of 2023, I sent a call out to find eight contributors for the second phase of my natural-hair campaign, ‘My Hair Is Not...’ It was important to me that I was sharing a diverse range of lived experiences and that someone could see this project and feel represented.

Creating a safe space to discuss such a sensitive topic was another intention of mine, and I feel privileged that the contributors were able to trust me and be open. The conversations I had with each person were powerful, thought-provoking, emotional and beautiful.

This photo story takes you on a journey through the lives of eight inspiring Black women, men and non-binary people, illuminating their unique experiences with their natural hair.

They had all been subject to microaggressions – insidious, often subtle, verbal, behavioural or environmental slights – in relation to their hair. These comments can be both intentional and unintentional, but they always convey hostile, derogatory or negative attitudes toward stigmatised or culturally marginalised groups.

“Is that your real hair?”

“Why don’t you just brush it?”

“It would look so much better straight.”

“It doesn’t look professional.”

“Can I touch it?”

“Oh! It’s softer than it looks!”

“Do you wash it?”

Multi-disciplinary artist, content creator and performer.

Darkwah Kyei-Darkwah

My relationship with my hair is sacred. It's connected to me, it's my soul.

I like to sit right in between all the energies. The energies of the binary, masculine and feminine, and all the others too. I like to be a nice double-take down the street.

When I was younger, I used to shave my head a lot, to try to make myself feel attractive. I was shaving off things that, at the time, made me feel ugly. When I started to let my hair grow, I began to discover what my hair could do for me. It unlocked a whole side of me that I had cut out, which was this femme, easy, sensual, I don’t know, kind of side.

A couple of years ago, at Trans Pride, I decided to wear my big Afro wig and someone I barely knew put their hands in my hair and said, “Ooh, this looks great.” I felt very violated and very angry. What in the world makes people think they have ownership over me? You don’t just go and touch something you don’t own.

We need to tackle these microaggressions in childhood; it needs to be spoken about in school. We need to have more material that empowers Black parents to put their children in those hairstyles and have those conversations. But we need our allies, mostly those who know that it’s not right, to stand up and say, “Wait a second, this school-uniform policy massively discriminates against this group of people.”

My hair has been so integral to me, ‘unlocking’ me. I used to read comic books when I was younger because I would escape into the mind of Jean Gray, Storm or Mystique. I would want to be them, and this hairstyle has literally made me feel like a comic-book superhero, like a princess, warrior, queen, whatever. I don’t care.

To anyone with the gift of this type of hair, grow your hair out. Connect with yourself. So many of us go through our lives hiding our hair, even from ourselves. That’s a whole sensory, emotional experience that you’re missing out on. So just at some point, do it. See what it unlocks for you.

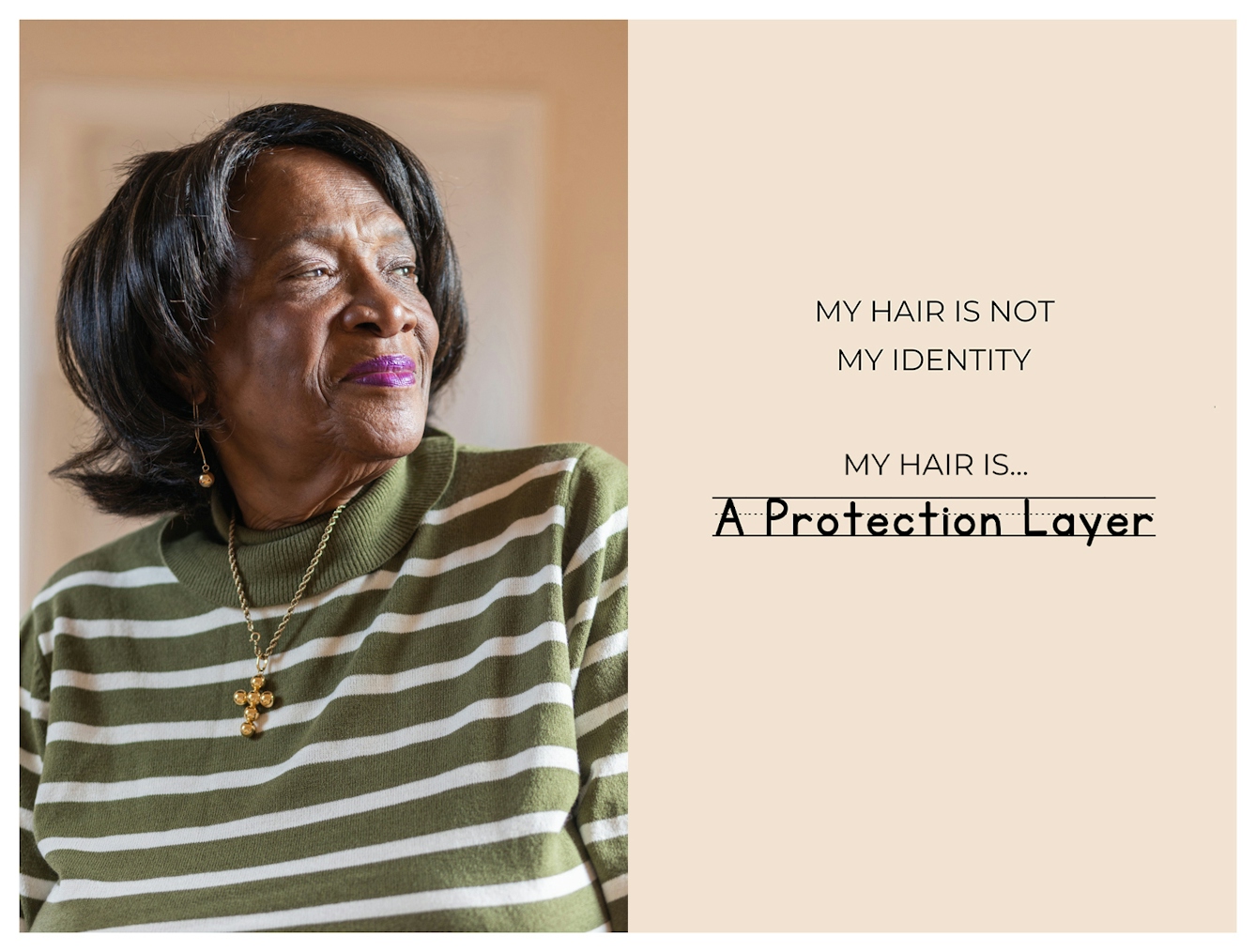

Retired, writer.

Heather Diana Yearwood

Like yourself first, before you put the wig on. Once you like yourself and aren't listening to what other people say, you can be be who you want to be. I'm still me without my hair.

I wear a wig to cover my sparse amount of hair; it just doesn’t grow much. I think I may have alopecia, because it’s very thin on top and thin on parts of the sides. I plait what can be plaited. I grease what can be greased, and I leave it alone. I don’t like how my hair lets me down, but there’s things called wigs and extensions and stuff like that you can wear. You can get them curly, short, frizzy, straight, blue, pink, green. So it doesn’t really worry me.

I’ve been wearing a wig practically all my life. I first came to Britain aged eight, and when I was about 13 or 14, my mother took me to the hairdresser’s to try out a wig, as my hair wasn’t growing beyond an inch. I looked in the mirror and I saw myself in this black wig and I thought, “Wow!” I looked good.

I remember when I went back to school after the summer holidays, everyone saying, “Oh, your hair’s grown.” I no longer got that bad feeling about my hair because I had my wig on. I didn’t want white people’s hair. I didn’t want Black people’s hair. I just wanted some hair.

I’m never ever gonna say that my hair is my culture. My culture is my behaviour and my feeling towards me and my fellow African. That’s my culture, because if I lose my hair, it doesn’t mean I’ll lose my culture.

Actor, singer and artist.

Isaiah Wamala

My hair has been with me for a long time, so I call it a ‘veteran’. It’s been through a lot of bad things, and good things, but it’s still here, loving me.

I love my hair – I’m not gonna lie. Before I didn’t really care about my hair that much. I always just left it how it was. I thought it looked nicer on me like that. But now I’m kinda scared to wake up and see my hair in a certain way. The first thing that I see near my bed is a brush and comb; it’s kinda scary, but I have a whole comb collection on my desk that I call my altar, with things that represent me and my connection to God.

At secondary school I was one of those kids that always brought a comb every single day in my blazer pocket. There have been a lot of people who have warned, as well as disclaimed me for my hair, calling me names and giving me advice. But one day there was a comment that I couldn’t forget, that shook me to my core. A random white person told me that my hair looked like tiny little dumbbells in jail cells where they put the black people. It left me shocked, and I never forgot it.

I feel like I respect my hair more than I ever did before. And I feel like I really wanna see how long it will grow. I guess I’m just finding my own connection with it, and then gaining some love as well.

Bionic playwright, screenwriter and filmmaker.

Matilda Feyiṣayọ Ibini

I definitely have a more patient relationship with my hair. I used to be very impatient when I was younger. And I think some of that impatience was also projected onto me by people that were doing my hair, or sometimes my mum. I have very thick, tight curls, which you could describe as like 4c hair, which often meant a lot of detangling. And I’ve got very vivid memories of using hot combs, or hair relaxers, or really tough wide tooth combs, spending ages just trying to detangle it.

My mum used to do me and my sisters' hair a lot, but when I moved out of the family home, and started living on my own, I realised I needed to find new ways of looking after my hair. Especially because I have a condition called limb girdle muscular dystrophy. This means I have a team of carers/PAs that support me, but a lot of them don’t necessarily have experience managing Afro hair. So part of the training is teaching them how to look after my hair.

It meant having to figure out new strategies, but also just accept that we live under a capitalistic structure that doesn’t afford us to have more time to look after our hair in the morning. I don’t have a spare 90 minutes just to do my hair, so we’ve had to find ways around that.

The very first time I ever shaved my head, I was in primary school, because relaxers had really damaged my hair. And once the relaxer wears off, it’s back to having very thick, tight, coily hair and I didn’t want to have my hair touched. So my mum was like, “If you don’t want hair, you know, you can shave it.”

I came back to school the next day, and people were misgendering me, and some people thought I was a new student. My teacher asked me to stand up and introduce myself. It was so embarrassing. But after that no one treated me any differently having a shaved head. I’m probably fortunate to have had a positive experience the first time I shaved my head, which is why I kept shaving if off every few years

I’ve come to understand all hair is good hair, irrespective of the type, the texture, the number, the letter. I’d say to people at the beginning of their journey, or who may not even realise that they need to go on a journey with their hair: take your time and you will get there. And hopefully you’ll unlearn some of those negative stereotypes about what it means to have Afro textured hair.

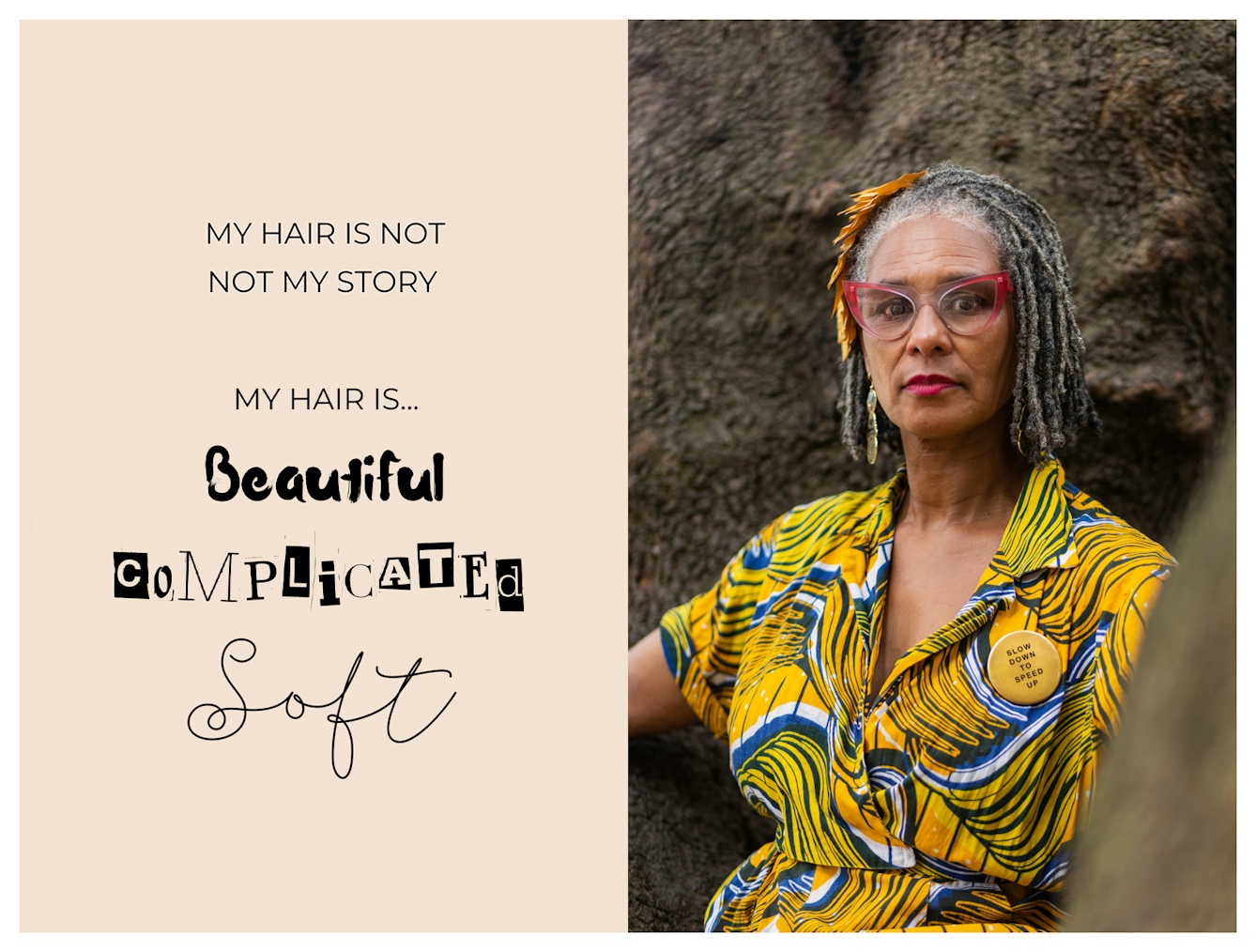

Fashion creative, podcast host and menopause activist.

Karen Arthur

We should embrace our hair in all its glory and different ways of being. Caring for our hair is a ritual, a beautiful process.

My hair is, it’s not me, really. I mean, it’s me in the sense that obviously I have a cut that suits me, but people can’t make assumptions just by looking at my hair and deciding that I should act in a certain way or have certain viewpoints

When I was young, I always had short hair. Everyone thought I was a boy, so my mum had my ears pierced, which I didn’t really want, but it’s your mum, right?

From about 14, my hair was longer, and I have fond memories of sitting between my mother’s knees on the floor and having her comb my hair. She’d rap my knuckles with the comb if I moved around or if I complained because it was hurting.

When I went to uni to study performing arts, I didn’t know how to do my hair, so I hooked up with the only other Black woman on the course. She taught me how to plait it at night for a fuller Afro in the morning. The first time I did it, it took me two hours to do six plaits, and when I combed it out in the morning, the top was flat and there was a step at the back.

I felt a sense of shame, actually. Shame that as a Black girl, my mother hadn’t taught me, and for a long time I blamed her for not teaching me about my heritage. But obviously, with hindsight, what could they do? They did the best that they could with what they had at the time, you know?

I’ve done all sorts with my hair. In the ’80s I spent a bit more money and started going to the hairdresser’s. I had it relaxed, which is a very strong chemical process and makes your hair look straight and Eurocentric, but it damages your scalp and it’s also carcinogenic.

My relationship with my hair has changed over time. When I was pregnant with my first child, my hair was lustrous and I had it relaxed into a bob. The minute I gave birth, my hair started to drop out, which was really traumatic. My partner at the time really liked my bob and if I'm honest I liked the proximity it gave me to whiteness, and I liked that he liked it. When it fell out, I was basing some of my worth on my hair and the way I looked. At that point I started to twist it.

Locking my hair has been the hardest and most fulfilling and rewarding hairstyle I’ve ever had. At first I would dye the grey out, but then I hit menopause and I just thought, “Fuck it, I’m not doing this any more.” I reframed my silver hairs as wisdom hairs – they’re beautiful. They’re my history, they tell my stories.

Queer scriptwriter, poet and visual artist.

Maheni Arthur

The beauty of Black hair is that it's so versatile. It's like a gift. It's not for anyone else, it's for you and it's your journey to hold.

I’ve recently started growing my hair out again after quite a few years of having a buzzcut, which I loved. And I’m definitely becoming more comfortable with the texture of my hair. I’ve got the kinkiest, oiliest, 4c-textured hair, which was difficult growing up – I always wanted it to be different. I just wanted it to be straighter and more manageable.

But now I feel really proud of it. I love the texture that I have. Because as I said, it’s mine. And you know, it’s a beautiful thing.

I used to have twists. My mum would always do my hair for school ’cos it just feels nice or whatever. And then when I got to 16 and I was going to college, I wanted a complete identity overhaul. So I shaved the sides and the back and then had it all on top. And I dyed it sort of like coppery red. And from then started a series of dyeing it different colours, and basically frying it.

I bleached it a lot and dyed it a lot, I think like five or six times. So it got to a point when my head was really damaged. And I didn’t want to get rid of it. And it was actually my mum, who was like, “We need to talk.” She was just trying to make me understand that my head wasn’t healthy and it was doing more damage to keep it than to not keep it.

It was actually really emotional when I cut it. Because hair is such a huge way that I like to express myself. So to get rid of that was really emotional. And then it became something that felt really like me. So it got shorter and shorter and shorter. And I wasn’t bleaching any more, but I was dyeing. I had braids for a few years. And when I cut it a second time, it felt like it was my choice to do it. Because I’d had long hair for so long. I buzzed it all off, and that felt like myself, that I had reached my final form.

You don’t necessarily have to love everything about yourself, but I think it’s a beautiful thing to at least accept something simply because it’s yours. Just because it doesn’t look like someone else’s or feel like someone else’s, it doesn’t mean that it’s not right. Trust the process, I would say, trust in the journey.

Product manager, author and model.

Zainab Kwaw-Swanzy

Your hair is good enough. Don't let anyone else tell you otherwise.

When I was younger, I didn’t really like my hair. I wanted to change it in order to fit in. I used to feel quite embarrassed by it. Hate is a quite a strong word, but I definitely didn’t like it for a long time. Then I started to focus on caring for my hair, just like you would care for any other part of your body. It took me on a journey of learning to love my hair and actually love myself and my identity.

My family and friends have mainly been a positive influence. When I was younger I had friends who weren’t Black and had straight hair that was viewed as beautiful, or they were Black and relaxed their hair or had weaves and wigs, which was also seen as beautiful. My friends never said anything negative about my natural hair, but the trends at the time made me feel negatively about it.

I’ve got two older sisters who experimented with their hair and wanted me to learn through their mistakes. Even though I wanted to relax my hair, they didn’t let me. They taught me over time that my natural hair was good enough and that’s why it was important to love it. I’ve been lucky to have grown up around lots of women who have always made me feel like every part of myself is beautiful, including my hair.

I’ve written and published a book called ‘A Quick Ting On: The Black Girl Afro’. It’s a book to celebrate Black women and their hair. It covers a range of topics, from history and culture to science, to business, to the impact of social media and technology on Black haircare.

For me, it’s a book that I wish I had when I was younger, to validate my own experiences and feel better informed about my hair. But it’s also a book that anyone can pick up and read and learn from and understand that Black hair has such a rich history.

Actress, writer.

Jo Martin

Our hair is beautiful. Embrace it, love it, care for it, and don’t hide it. Represent.

I love my hair. I went natural and stopped using chemicals about 20 years ago. But I didn’t locs up straight away, because in the older Caribbean community there was a kind of idea that if you’ve got locs you could become a drug addict, or you can go and do crime, which is nonsensical, you know.

As a young girl I hated my hair. If you grew up in the ’70s and ’80s as a woman with Afro hair, you were stigmatised in the sense that you would get a lot of insults like, “Your hair’s a Brillo pad.” When I left home, I got into this whole notion that I’d gotta wear a weave, you know. I’m going to put that on because I’ll fit in more. That hatred of my beautiful hair pains me even now.

As an adult, when I went natural, I was wearing my hair as an Afro with all the tips died red, making a halo – it looked wicked. But a lot of European people would want to touch it, like you’re some kind of dolly. Sometimes I’d feel too embarrassed to find my voice, to say, “No, I don’t want you to touch my hair,” because then you turn it into a ‘thing’ and look like the bad guy.

As an actor I’ve been in a professional situation where my character, a neurosurgeon, has been scripted to wear a European-style wig to hide my locs. But I said, “She can have locs – go to Jamaica or Ghana and you’ll see them.” There are people in high-status jobs with locs. There was a bit of a battle, but there were a couple of producers who were very supportive, you know; I thought it was important to represent my locs.

So my relationship with my hair has changed greatly, and I’m so glad. It’s such a freeing feeling to embrace who you are. If you try to invent what’s not you – your sexuality, your abilities, your hair, your colour, your culture – you in problems.

About the photographer

Inés Yearwood-Sanchez

Inés Yearwood-Sanchez is a mixed-heritage documentary photographer and activist from London. Her work primarily focuses on identity and culture, and she has exhibited in various cultural institutions across London. Inés has also worked on a brand campaign for Beats by Dre in collaboration with Black Girl Fest. She has recently graduated from university and is currently doing an internship at BAFTA in the Learning, Inclusion & Talent team.