Before a vaccine was available, diphtheria was a much-feared disease of childhood, killing 20 per cent of the under-fives that contracted it. French researchers who developed an antitoxin from horses’ blood at the end of the 19th century were rightly hailed as saviours, but contamination presented frightening challenges. This is how Jim, a retired ambulance horse, inadvertently prompted the start of governmental control over medical products.

Jim, the horse of death

Words by Chris Bakeraverage reading time 4 minutes

- Article

It was the “scourge of childhood”, or “the strangling angel of children”. And as it ripped through the densely populated cities of the industrial age, spreading easily with coughs and sneezes, diphtheria was a disease that had earned its gruesome epithets.

One in ten patients died. One in five if they were children under five. Gasping for breath and unable to swallow, they choked to death on a tough grey membrane that had formed in their throat. Made up of dead human cells killed by a toxic protein, this membrane was the product of a bacterium. A bacterium that lodged in the upper respiratory tract and steadily secreted that poisonous protein.

For six-year-old Bessie Baker, though, the outlook was good. It was 1901 and her hometown, the American city of St Louis, had made sure that its citizens had access to the latest medical technologies. When a doctor diagnosed Bessie with an advanced case of diphtheria, he knew what to do: he injected the girl with diphtheria antitoxin. Well aware of the ease with which the disease spread, he also injected her two younger siblings.

Four thousand miles from St Louis, scientists working in France and Germany had identified that animals infected with small amounts of diphtheria produced something in their blood that could be used to treat the disease in other animals. They called that something an antitoxin, and in 1894, bacteriologist Émile Roux (1853–1933) announced that antitoxins produced in the blood of horses had halved diphtheria mortality in his Paris hospital.

Within a year, the Health Commission in St Louis had established a factory farm of its own, where white-coated orderlies injected horses with diphtheria toxin and, once the horses were fully immune, collected litres of blood from veins in their necks. Left to stand, the blood separated into a dark red coagulate and a clear, yellow liquid. It was this liquid that the doctor had injected into Bessie Baker. A liquid, we now understand, packed with diphtheria antibodies.

But when the doctor called to see Bessie again, four days later, he did not encounter the healthy young child he expected to see. Her condition had worsened, and the muscles of her face were tight and stiff. Within a week, all three Baker children were dead. They were three out of 13 St Louis children who died that autumn, following injection with diphtheria antitoxin.

An early wave of vaccine hesitancy

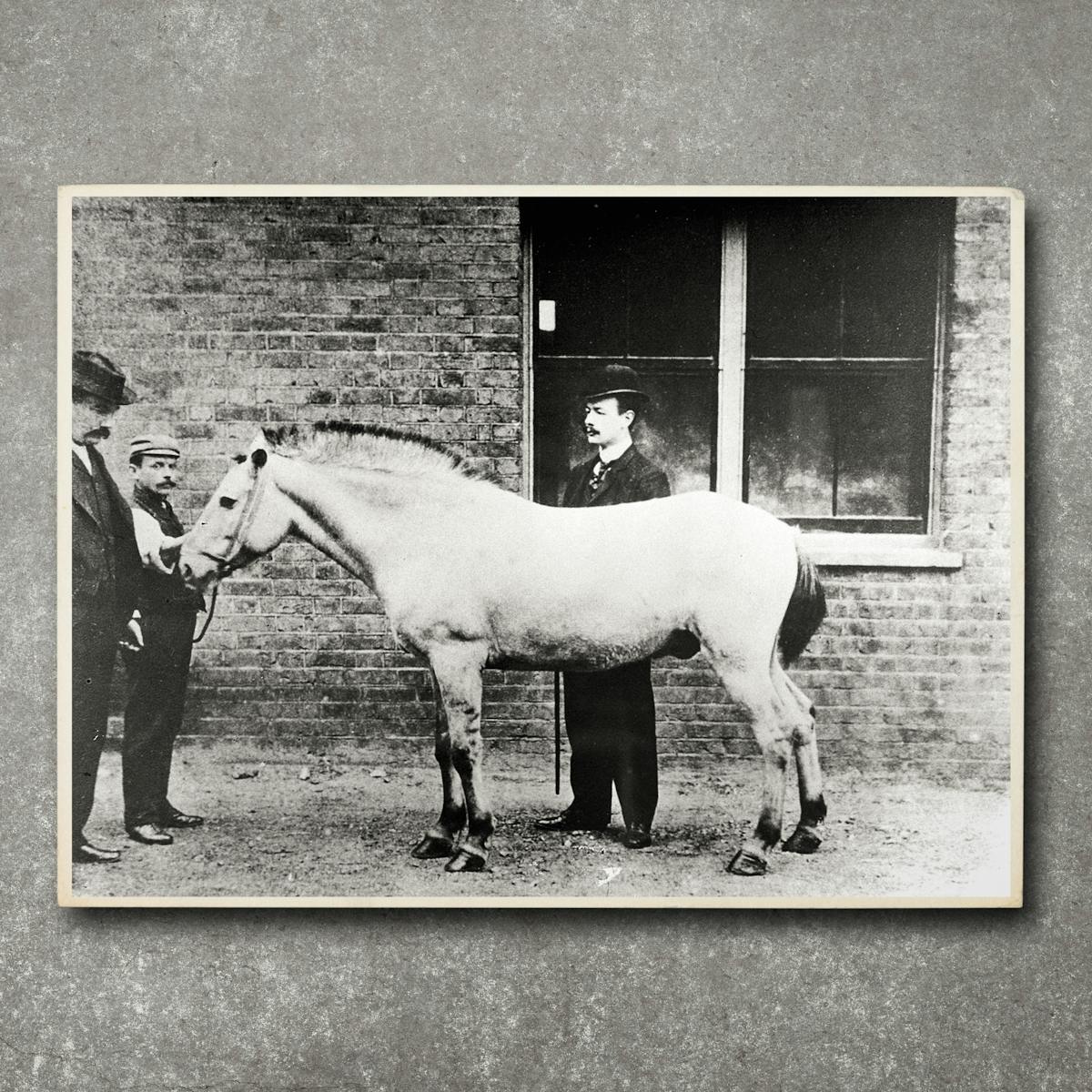

The symptoms the Baker children had exhibited before death, though, were not those of diphtheria: the tight, stiff muscles of the face were characteristic of tetanus. All of the dead children had received antitoxins from a retired ambulance horse called Jim and, one month earlier, Jim had been diagnosed with tetanus.

Like Bessie’s doctor, the scientists working on the farm had known what they needed to do. Since there was a risk of tetanus transmission, they euthanised Jim, and they ordered the destruction of every sample produced from his blood. The samples weren’t all destroyed, though, and 13 children died of an infectious disease transmitted in a medicine designed to keep them safe. Parents across the United States refused diphtheria antitoxin for their children; in Chicago, the diphtheria death rate increased by a third.

The staff of the St Louis farm might have been negligent, but they had broken no laws. There were no laws: manufacturers of biological products were almost entirely unregulated. But now the government had to act, and in 1902 Congress passed the Biologics Control Act. Manufacturers of antitoxins and vaccines had to be licensed, were regularly inspected, and had to conform to specified standards in the labelling of products.

Many went out of business, and the City of St Louis never produced another vial of diphtheria antitoxin, but confidence in the quality and safety of modern medical products steadily increased. When diphtheria vaccination was introduced to the USA in the 1920s, it was to widespread acceptance.

Elsewhere, the lessons of St Louis often had to be learned anew. In Australia and Ireland, children died from diseases contracted from contaminated diphtheria vaccines, and confidence in vaccination collapsed before regulations were tightened.

In the UK, those overseas incidents raised concerns that helped delay the introduction of large-scale diphtheria vaccination until 1940. In that year, England and Wales recorded 2,480 diphtheria deaths, while the USA – which had recorded more than 16,000 in 1920 – suffered only 1,500. Jim the horse had caused the deaths of 13 children, but his legacy was to save thousands more.

About the author

Chris Baker

Chris Baker is a professional scientist and freelance writer based in Wiltshire, UK. As a writer, his focus is on stories at the points where science and technology intersect with geography and history.